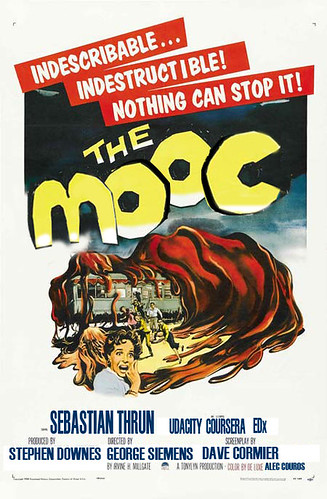

Credit: Photo by Giulia Forsythe under a

CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 License

I recently successfully finished my first massive open online course (MOOC). It was the 6-week Gamification course on the new Coursera platform, presented by Kevin Werbach of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. It wasn’t the first MOOC I’d ever started but it was different in its underlying approach than the others. This post contextualizes the Coursera MOOC platform prior to discussing whether it succeeds or not in a later post.

The Early MOOC

Connectivism and Connective Knowledge (CCK09) in 2009 was the first MOOC I think I participated in, although I may have dipped in and out of the inaugural one a year prior. I certainly remember more about Personal Learning Environments, Networks, and Knowledge (PLENK2010) run the next year. That MOOC, facilitated by George Siemens, Stephen Downes, Dave Cormier, and Rita Kop, and others they ran were organized similarly. The course had a website hosting a sign-up facility, a syllabus and general course information, links to the online presentation rooms, and usually forums. Students were encouraged to explore a given topic space, aggregating resources. They were aided by the facilitators who produced some appropriate content and either gave a presentation each week or invited someone else from the educational technology community to do so.

From these resources and influenced by content contributed by other course participants, students would produce their own content in the form of blogs, movies, mindmaps, etc. These would be shared with other participants and there was an ethos that encouraged remixing or repurposing content. Each day, a newsletter would be mailed out to participants, highlighting some of the recently produced artifacts. You could also search around the web for the #PLENK2010 hashtag or subscribe to an RSS feed of participant blog posts. It was many-to-many.

The Coursera MOOC

PLENK2010 was completely unlike the Coursera offering. The Gamification course had the following elements: a course site with the latest news, a syllabus, the course lectures, multiple choice quizzes, written homework assignments, and the forums. The course content consisted of 12 units, with each unit containing five or six 8-to–15-minute videos. A few videos were interviews with other people, but the majority were Kevin Werbach addressing key concepts.

It was a structure that encouraged passive consumption. That’s not to say students weren’t encouraged to work with the material. Some videos contained one or two simple multiple choice questions embedded within them and many contained “reflection exercises” where the watcher was asked to think about something, write down a response, and then share it later in the forums. The forums also provided space to arrange meetups and local study groups. Certainly the Twitter #gamification12 tag saw some good use. Some students did write blog posts and others contributed to a wiki or to preparing and sharing video annotations. However, for the majority of students, the only content production would have been forum posts, the written assignments, or peer feedback.

With this type of structure, very early on I found myself musing how Coursera was any different to the Open University, for whom I’ve taught online since 2001, or any other higher education institution with course content online. Coursera basically appeared to be an LMS or VLE. Sure, it operated on a large scale per course, even larger than that of the Open University, but still a VLE. Sui Fai John Mak is a regular contributor to the connectivist MOOCs I’ve previously joined and a collaborator on some peer-reviewed papers around MOOCs and a pedagogy of abundance. In a recent blog post, he described MOOCs in this style as “flipped classrooms”, but ones still based on the instructivist approach.

xMOOC is based on the teaching model where the teacher teaches, and the students learn and consume the knowledge from the course, like watching the videos, or reading a book, an artifact, and be assessed on what has been taught or covered in the videos. … [It] is STILL based on the instructivist approach – which is based on behavioral/cognitivist learning theory, where the learners master the content, probably with the transfer of knowledge from one person or a number of persons (the professor(s)) or the machines (robot or virtual teacher), or information source to that of the learner. (Mak 2012) [1]

The “flipped” part, explained earlier in the post, is that the “classroom” is used for the interactive parts, while the content and some exercises are completed by the students at home. It’s still, however, basically the traditional approach to learning. It is the classic “sage on the stage” approach (King 1993)[2] but one-to-very-many.

xMOOC versus cMOOC

4 Oct @Eingang said:

@laurapasquini @gsiemens Just using the acronym MOOC, they have it covered. I suspect we’ll be forced to adopt a new term for our “brand”

4 Oct @Eingang said:

@laurapasquini @gsiemens Coursera et al latched on to the “open” (read: free) & “massive” parts but not the connectionism/rhizome parts.

4 Oct @Eingang said:

@laurapasquini Coursera IMO is not any different than the Open University in terms of how and how many. Neither a @gsiemens MOOC.

4 Oct @Eingang said:

I keep saying this >; RT @laurapasquini: Actually #mooc was around a long time before AI, Coursera & more. Right @gSiemens #rockstarteacher

On Twitter I was commenting on how we’d need a different term to differentiate between the (for me) “traditional” connectivist-based MOOC and the new MOOCs by Udacity, Coursera, and similar. Nobody embarrassed me by pointing out that it had been done while I’d been on an extended vacation earlier this year.

We now have “xMOOC” to describe the Coursera-type offerings and “cMOOC” for the connectivism-inspired approaches. George Siemens (2012)[3] succinctly defines the difference as “… cMOOCs focus on knowledge creation and generation whereas xMOOCs focus on knowledge duplication. ” or pithily as @MarkSmither’s other half put it: “in an xMOOC you watch videos, in a cMOOC you make videos.” So true!

Despite their pedagogical differences, the two approaches share some characteristics, not all of which can be seen as good. In a follow-up post, I’ll consider the practical issues of courses with tens of thousands of students as experienced as a participant in the Gamification xMOOC, contrasting them with some of the issues as I perceived them for participants in cMOOCs.

References

-

Mak, S.F.J. (2012) ‘In MOOCs, more is less, and less is more (part 2)’, Learner Weblog: Education and Learning weblog, blog entry posted September 12. Available at: http://suifaijohnmak.wordpress.com/2012/09/12/in-moocs-more-is-less-and-less-is-more-part–2 (Accessed October 19, 2012).

-

King, A. (1993) ‘From sage on the stage to guide on the side’. College Teaching, 41 (1), pp:30–35. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/pss/27558571.

-

Siemens, G. (2012) ‘MOOCs are really a platform’, Elearnspace: Learning, Networks, Knowledge, Technology, Community, blog entry posted July 25. Available at: http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/2012/07/25/moocs-are-really-a-platform/ (Accessed October 19, 2012).